with

Learn more

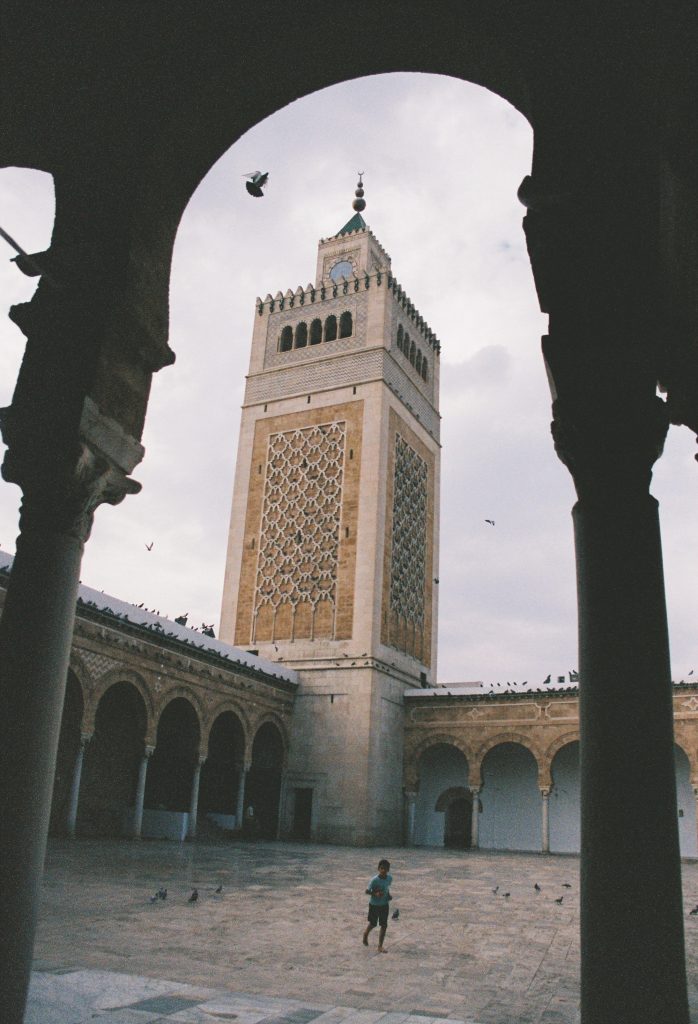

Echoes From the Sea

A journey through Taormina, Italy, and Tunis, Tunisia, reveals how the Mediterranean’s layered histories continue to speak today.

On a crystal-clear day in September, Mohammed—my guide to the ancient ruins of Carthage—took me up to a plateau in Tunis, the capital of Tunisia. This spot in the North African country overlooks harbours that were first built by the Phoenicians nearly 3,000 years ago. Behind me, a Catholic church built by the French in the late 1800s was just reopening after a refurbishment. There were ancient columns beside me as well. Mohammed explained that they are remnants of the town forum, built by the Romans in the first century B.C. and themselves standing on the ruins of the ancient city of Carthage. The striations of human history appeared piled up in one tableau, all of it glittering in Mediterranean sunshine, overlooking the brilliant blue sea.

Along the shores of the Med, one doesn’t have to search too terribly far to find this sort of layering of story, influence, and civilizations. Any lover of history knows that Muslim rule extended for nearly 800 years in parts of the Iberian Peninsula, which left a lasting influence on Spanish architecture. Other connections are less widely known. During my recent visits both to Tunis and to Taormina, in northeastern Sicily, echoes of the region’s interconnected past were all around me.

Taormina

Sicily itself lived under Islamic rule for more than 200 years, starting with an invasion by the Aghlabid dynasty (which ruled what is now modern-day Tunisia) in 827 A.D. The conquest of the island was complete in 902 A.D. with the fall of Taormina. This ancient city winds up the slopes of Monte Tauro like something out of a fairy tale, with commanding cliffside views of the ocean that simply stop you in your tracks.

Checking into San Domenico Palace, Taormina, A Four Seasons Hotel, is like entering a walled garden in paradise. Once a hilltop redoubt for the Dominican order, the onetime monastery, which served as a hotel as early as 1896, has both Arabic and Italian architectural influences, highlighted by a central plaza. The real centrepiece of the property, though, is the garden, where the smell of hibiscus rises in the afternoons. According to the hotel’s art concierge and tour guide, Margaret Ranieri, this is where monks would have contemplated the bounty of nature while looking out over the Ionian Sea.

As we walked through Taormina’s old town—passing vignettes seen in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1960 film L’Avventura—Ranieri led me through the city’s various histories. “The visitors arrived like the tides,” she said. And many of the famous travellers who came to Taormina—from Oscar Wilde and Greta Garbo to Gustav Klimt and D.H. Lawrence—were in search of refuge. The town has always been a tolerant place that can receive the tides, she noted.

In Sicily, you can find historical links to many parts of the Mediterranean. The church in the centre of Taormina, for example, has a catacomb with bodies mummified in the ancient Egyptian manner. Witness, too, around town the frequently used symbol of the elephant, employed in some cases to protect against Mount Etna’s “moods,” as Ranieri called them. It is even possible, Ranieri said, that the skulls of the long-extinct dwarf elephants that made their way to Sicily from Africa in ancient times, with their enormous central cavity, gave rise to the legend of the Cyclops that appears in Homer’s Odyssey.

On our tour, when we reached the famed Ancient Theatre of Taormina—originally built by the Greeks in the third century B.C.—Ranieri invited me to think about catharsis. She was referring to the ancient Greek sense of the word, the way Aristotle used it to mean a kind of cleansing of the mind and spirit that comes from contemplation of nature, or, indeed, of the drama in a theatre. Looking down the mountain from this ancient temple built for a kind of exaltation, I thought I rather understood: my mind felt radically clear.

From the theatre’s cafe, there is a clear view of ferries crossing the Strait of Messina toward the Italian mainland and heading to points elsewhere as well. As the filmmaker and photographer Andrea DeFusco tells me, ferry culture and the seaborne journey is still very romantic in the minds of Italians, here where the likes of the Argonauts and Odysseus once roamed.

DeFusco is developing a book about Sicilian ferries with his brother Giacomo, and he rides the boats from the mainland every year. “You board,” he says, of his preferred overnight ferries, “and night quickly falls. At that point, it’s as if you were nowhere anymore—the land has disappeared beyond the horizon. You are simply on the ship, on a moving island. Even the idea of time fades away.”

Tunis

Culture exchange is evident on menus everywhere in Tunis.

On a map, Sicily and Tunisia look like they could have touched at some distant point back in time. The Sicilian port of Marsala (the Saracen people reverentially called it Marsa Allah, or “Harbour of Allah”) on the western side of the island is, after all, only around 130 miles by sea from Tunis, and a 10-hour-plus ferry runs approximately two times a week from Palermo, Sicily, to the Tunisian capital.

I made my way to North Africa not nearly as directly, flying from Sicily to Rome and then on to Tunis. Immediately on arriving in Tunis, I was attuned to the linkages—in architecture, in design, in aspect—reverberating across the Strait of Sicily, from painted tiles reminiscent of the blue-and-white tiles in Taormina to, of course, Roman columns found in the ruins in the capital. In fact, a recent show at the Ahmed Bey Palace in the Tunisian coastal city of La Marsa explored the Italian influence in the architecture of Tunis from the 1600s through the 20th century.

Culture exchange is evident on menus everywhere in Tunis. There are caponata-style stews—maybe the most iconic of Sicilian dishes but made with ingredients and practices first brought to the Italian island by North Africans—and plenty of traditional Tunisian dishes with pasta, some blending the sour and sweet flavours most identified with Sicilian cuisine: agrodolce sauce. The town of La Goulette, not far from the city centre, expanded significantly in the 19th century due to a wave of emigrants from Sicily, and until recently was still referred to as Petite Sicile, or “Little Sicily.”

Near Tunis, on the coast about a 20-minute drive from the Medina, lies the town of Sidi Bou Said. Known for its blue-and-white houses and for looking a bit like the kasbah of Tangier, it hugs a hilltop with 270-degree views of the water. At Bleue!, a lo-fi, high-vibes café and deli, owners Katherine Li Johnson and Reem Al Hajjej offer locally sourced salads and sandwiches and sell great merch. It’s a buzzing community hub. As the Tunisian German fashion designer Lamia Lagha tells me, Bleue! is the place to go to meet everyone in the art and music and design scenes—and to find out where the best concerts and parties are.

A short drive north of Sidi Bou Said, past the grand old corniche of Marsa, the vibe shifts. Four Seasons Hotel Tunis is a sort of village unto itself, made up of modernist cubes hugging a scene-y pool and the Mediterranean-style Blu Seafood Kitchen & Bar, which leads to a private beach cove. There’s a feeling of refuge. Here, on the edge of the African continent, looking out on the sea as it goes from a shimmering aqua at midday to a dusty mauve after the sun sets, you can feel both way, way out there and in the very centre of the world, cloistered and connected, like the Sicilian monks on their clifftop perch.

The feeling of being suspended between worlds stayed with me. On the afternoon that Mohammed showed me the Roman forum, he also took me to the ancient amphitheatre of Carthage—still a busy cultural venue hosting concerts and festivals—which is almost a perfect mirror of the theatre in Taormina. As we walked up the steps, past the ruins of the neighbourhood where the Roman patricians had their villas, Mohammed and I admired the commanding view of the sea. It seemed yet another perfect place for catharsis, and an ideal vantage from which to contemplate the layers of time.

More like this

art and design fashion

The Distinction List: 25 Trends for the New Era of Luxury

From covetable creations to exceptional stays and refined dining, Four Seasons magazine curates the defining trends shaping the next era of luxury.

restaurants

Caviar—But Make It Casual

Roe gets a laid-back remix, topping everything from potato chips to fried chicken.

Trending

-

Palm Beach Confidential: Landscape Architect Fernando Wong Shares His City’s Gems

The celebrated designer offers his personal guide to Florida's sun-soaked coastal enclave.

-

Bring The Four Seasons

Experience HomeRest peacefully on the world’s most comfortable mattress.

-

Opinion: In Defence of Luck

In the success equation, luck plays an important role.